Building a Virtual Production Studio From Scratch

With no virtual production experience, a two-person team, and a daily live stream still running every morning — we had to figure out Unreal Engine, Aximmetry, and Blender to deliver 40 instructional videos for an Italian bank client.

The Brief

At TraderTV.LIVE in 2021, myself and one colleague were running all production and technical work for a daily YouTube live stream about day trading. Two people handling everything. Directing, switching, cameras, audio, graphics, the full broadcast chain. We were using a Blackmagic ATEM Constellation 4 M/E switcher with a Behringer X32 audio mixer.

Then we landed a client. An Italian bank wanted to collaborate on 40 instructional videos covering market fundamentals. And someone decided we were going to do it using virtual production.

Learning on the Job

Neither of us had ever done virtual production. We had green screen experience with static keyed backgrounds behind the hosts, but nothing with tracked cameras, real-time 3D environments, or game engine compositing. Virtual production was just starting to break into the mainstream. The Mandalorian had shown what was possible with LED walls, and some news networks were experimenting with real-time graphics. But we’d never touched any of it.

The timeline didn’t give us the luxury of a course or a training period. We were still running the live stream every morning. In the afternoons, I’d sit down and start learning. Unreal Engine for real-time rendering, Aximmetry for compositing and virtual camera control, and Blender for building the 3D environment.

The Physical Setup

The studio was built for the daily live stream, not for virtual production. We had three desks. Two were trading stations equipped with computers and multi-monitor setups, with multiple Blackmagic Micro Studio Cameras for shots of the hosts at these desks and their screens. The third desk was the host position, covered in green fabric with a retractable green curtain that could be pulled around behind it. During the show, this desk was used for market updates and commentary. One host would sit there with a computer and two low-angled monitors while the main action happened at the trading stations.

For cameras, we had three television studio-grade pedestals with Blackmagic Studio Cameras mounted on them. During the live stream we’d move them around the studio for different segments. That was our entire camera inventory.

Working Within the Constraints

For the virtual production recordings, we were limited to those same three pedestal cameras. We had no camera tracking system. No encoders, no sensors, nothing feeding position data into the virtual environment. Every virtual camera angle had to be locked off and precisely matched to a physical camera position by hand.

After wrapping the morning live stream, we’d move the cameras into their virtual production positions. We marked the floor with tape for each pedestal placement and measured the height, tilt, and zoom of each camera head so we could reset them consistently between sessions. Any time a camera position was off, even slightly, the virtual environment wouldn’t line up with the physical green screen edges and the composite would break.

This meant we couldn’t do live camera moves during recording. Every shot was essentially locked off. The “camera movement” the viewer sees in the final videos is all virtual, triggered through Aximmetry’s preset system and composited in real-time.

We also had to direct the talent. The hosts were keyed out and placed behind the virtual desk in Aximmetry, literally layered behind the 3D model. The real desk was green and keyed out, but the monitors and the hosts’ hands resting on the desk were still visible. This is where camera height and positioning became critical. If the camera was even slightly too high or too low, the hosts’ hands would clip through the virtual desk. Every measurement had to be precise enough that the physical desk surface and the virtual desk surface lined up exactly.

The virtual desk itself looked great. I gave it a reflective texture in Unreal Engine, and Aximmetry handled real-time reflections of the hosts on the desk surface. It sold the illusion that they were actually sitting at this thing.

One camera had the wide shot of the full desk, and the other two were close-ups on two of the hosts. Without camera tracking, the keyed output from each camera was essentially a floating 2D cutout of the host composited into the 3D scene. To make it look less flat, we deliberately placed the two close-up cameras off to the side rather than straight on. Seeing the hosts at a slight angle gave the composite more of a 3D feel, even though there was no actual depth information. It was a small decision but it made a noticeable difference in how convincing the final shots looked. Because of the layering, any movement that extended past the edges of the virtual desk would break the illusion. I had to instruct the hosts to keep their hands tucked in as much as possible and limit their movement. It was a constant balance between keeping them comfortable enough to deliver naturally and keeping the composite clean.

The Virtual Studio

I modeled the virtual studio in Blender, a full 3D set designed to look like a professional broadcast environment. That model was brought into Unreal Engine as the real-time rendering environment, and Aximmetry handled the compositing layer between the game engine and our broadcast hardware.

The physical host desk was keyed out entirely and replaced with the 3D desk in the virtual environment. The green curtain behind it gave us a full backdrop for wider shots.

We built out the Aximmetry node graph to add real functionality to the virtual set. The TV screens inside the virtual studio could take live video feeds via SDI through a Blackmagic DeckLink card, or switch to static images. We created virtual camera presets and custom camera moves inside Aximmetry.

The Switching Workflow

It was kind of hacky, but it worked. Because of PCIe limitations on the rendering PC, we only had a single program output from Aximmetry feeding back into the ATEM. That was our entire virtual production pipeline in one video feed.

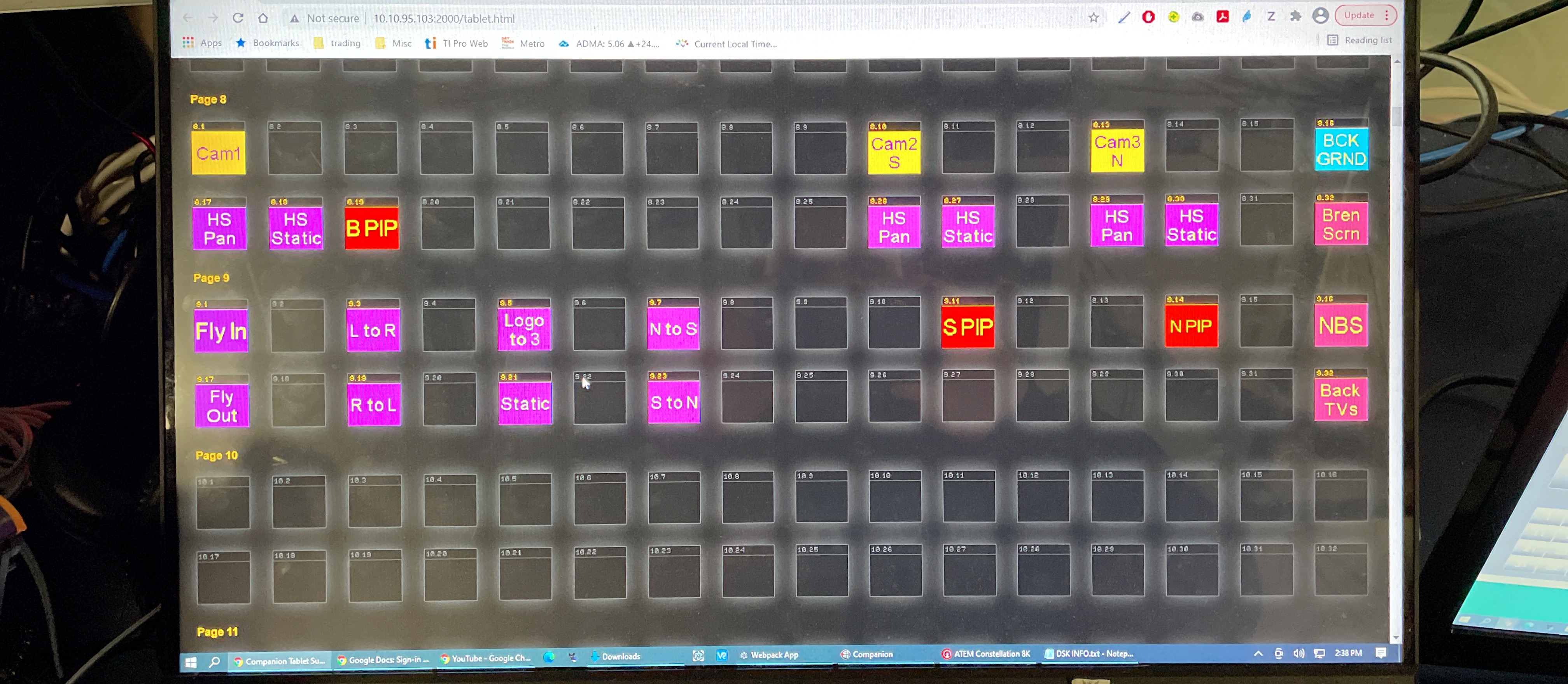

Companion handled the Aximmetry side. Buttons triggered virtual camera moves and changed what was on the Aximmetry program output. The ATEM side used that Aximmetry program as one source alongside raw SDI feeds of the hosts’ screens. We built ATEM macros that combined these into SuperSource layouts. One macro might call a SuperSource with the Aximmetry close-up in one box and a host’s screen in another. Another macro would switch to a different SuperSource with the screen larger and the background behind it.

The Companion buttons and ATEM macros worked together. A button press would trigger a virtual camera move in Aximmetry while simultaneously calling an ATEM macro to switch SuperSource layouts. To hide the virtual camera snapping between positions, we’d cut to a SuperSource that featured a host’s screen, then cut Aximmetry to the wide virtual camera shot so that was ready. While the wide was sitting there not visible to the viewer, we’d reposition the close-up virtual camera in the background. Then cut back to it once it settled.

Every transition was choreographed this way. Companion controlling the virtual cameras, ATEM macros handling the SuperSource compositions, and the timing between them keeping the viewer from ever seeing the seams.

The Problems

Audio/video synchronization. We were feeding video through a DeckLink PCIe card, and the audio and video were falling out of sync. We suspected it had to do with PCIe lane allocation on the PC, and I tried several fixes, but nothing resolved it reliably. We didn’t have time to keep troubleshooting. These were meant to be live-to-tape recordings, and the client deadline wasn’t moving. We decided to fix the sync in post.

Post-Production at Scale

After recording, we had to edit and deliver all 40 videos. Each one needed a custom intro with a unique title, a custom outro, and subtitles. And every video had to be delivered twice. Once with English subtitles and once with Italian.

We built an After Effects template system for the intros and outros so that swapping titles was fast and consistent. For subtitles, one of the team members built an automated workflow. He’d generate an SRT file for each video and we’d drop it into the project. Audio sync correction happened here too, aligning the shifted audio across every edit.

That left us with 80 final renders. 40 English, 40 Italian. And only a few days to deliver. One machine wasn’t going to cut it, so we set up a render farm using PCs from around the office, pulling whatever was available and farming out renders across multiple machines to hit the deadline.

What It Proved

Looking back, this was the first time I took on something completely outside my skillset and figured it out under pressure. No training budget, no senior engineer to ask, no extra staff. Just two people, a daily show still running in the morning, and an afternoon to learn game engines and 3D compositing.

It also planted the seed for everything I’ve built since. The idea that broadcast hardware and software don’t have to stay in their own lanes. That an ATEM, a game engine, and an automation tool like Companion can all talk to each other and create something none of them could do alone. That same thinking is behind every project on this site.